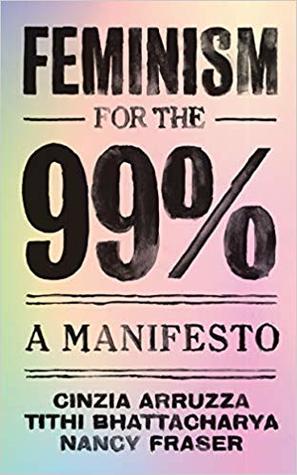

Book Notes: Feminism for the 99%

Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto

by Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, Nancy Fraser

Read

Jun 17, 2020 -

Jun 21, 2020

⭐⭐⭐⭐

Feminism for the 99% is structured as a list of theses that present a truly inclusive, people-centered feminism. This s a feminism that recognizes the overlaps between gender and many other systemic issues – racism, environmental threats, capitalism, etc – which need to be resolved before a truly feminist justice can be realized.

The theses revolve around intersectionality of struggles, as well as axes of opression. They include ideas like “Gender violence takes many forms, all of them entangled with capitalist social relations” (thesis #6) or “Fighting to reverse capital’s destruction of the earth, feminism for the 99 percent is eco-socialist” (thesis #9). Each thesis is examined in turn, providing a fairly comprehensive analysis, despite its brevity.

Book Highlights

Will we continue to pursue “equal opportunity domination” while the planet burns? Or will we reimagine gender justice in an anticapitalist form—one that leads beyond the present crisis to a new society?

Breaking through the isolation of domestic and symbolic walls, the strikes demonstrate the enormous political potential of women’s power: the power of those whose paid and unpaid work sustains the world.

By making visible the indispensable role played by gendered, unpaid work in capitalist society, it draws attention to activities from which capital benefits, but for which it does not pay.

In treating women simply as an “underrepresented group,” its proponents seek to ensure that a few privileged souls can attain positions and pay on a par with the men of their own class.

Our answer to lean-in feminism is kick-back feminism. We have no interest in breaking the glass ceiling while leaving the vast majority to clean up the shards.

But capitalism established new, distinctively “modern” forms of sexism, underpinned by new institutional structures. Its key move was to separate the making of people from the making of profit, to assign the first job to women, and to subordinate it to the second.

Because capital avoids paying for this work to the extent that it can, while treating money as the be-all and end-all, it relegates those who perform social-reproductive labor to a position of subordination—not only to the owners of capital, but also to those more advantaged waged workers who can offload the responsibility for it onto others.

class struggle includes struggles over social reproduction: for universal health care and free education, for environmental justice and access to clean energy, and for housing and public transportation.

The gender violence we experience today reflects the contradictory dynamics of family and personal life in capitalist society.

While appearing to valorize individual freedom, sexual liberalism leaves unchallenged the structural conditions that fuel homophobia and transphobia, including the role of the family in social reproduction.

Even where they were not explicitly or intentionally racist, liberal and radical feminists alike have defined “sexism” and “gender issues” in ways that falsely universalize the situation of white, middle-class women.

nothing that deserves the name of “women’s liberation” can be achieved in a racist, imperialist society

The social wage is declining as well, as services that used to be provided publicly are offloaded onto families and communities—which is to say, chiefly onto minority and immigrant women.

But abstract proclamations of global sisterhood are counterproductive. Treating what is really the goal of a political process as if it were given at the outset, they convey a false impression of homogeneity.

It was not “humanity” in general but capital that extracted carbonized deposits formed over hundreds of millions of years beneath the crust of the earth; and it was capital that consumed them in the blink of an eye with total disregard for replenishment or the impacts of pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

women’s struggles focus on the real world, in which social justice, the well-being of human communities, and the sustainability of nonhuman nature are inextricably bound up together.

By virtue of its very structure, therefore, capitalism deprives us of the ability to decide collectively exactly what and how much to produce, on what energic basis, and through what kinds of social relations.

Struggle is both an opportunity and a school.

Contra narrow, old-school understandings, industrial wage labor is not the sum total of the working class; nor is its exploitation the apex of capitalist domination. To insist on its primacy is not to foster, but rather to weaken, class solidarity.

As feminists, we appreciate that capitalism is not just an economic system, but something larger: an institutionalized social order that also encompasses the apparently “noneconomic” relations and practices that sustain the official economy.

“Social reproduction” refers to the second imperative. It encompasses activities that sustain human beings as embodied social beings who must not only eat and sleep but also raise their children, care for their families, and maintain their communities, all while pursuing their hopes for the future.

Social practices that nourish our lives at home, and social services that nurture our lives outside of it, constantly threaten to cut into profits. Thus, a financial drive to reduce those costs and an ideological drive to undermine such labors are endemic to the system as a whole.

On the one hand, the system cannot function without this activity; on the other, it disavows the latter’s costs and accords it little or no economic value.

In comparison with the postwar era, the number of hours of waged work per household has skyrocketed, cutting deep into the time available to replenish ourselves, care for our families and friends, and maintain our homes and communities.

Capital’s assault on social reproduction also proceeds through the retrenchment of public social services.

But Marx’s followers have not always grasped that neither the working class nor humanity is an undifferentiated, homogenous entity and that universality cannot be achieved by ignoring their internal differences.

This last highlight ties into a thought from Angela Davis’ Freedom is a Constant Struggle about what she calls the “tyranny of the universal”:

For most of our history the very category “human” has not embraced Black people and people of color. Its abstractness has been colored white and gendered male.