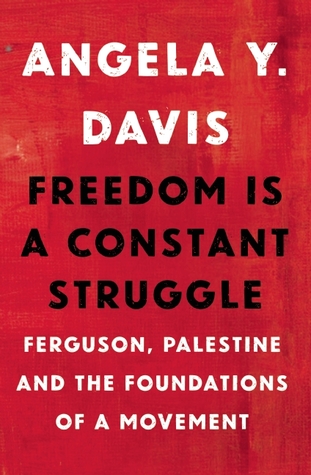

Book Notes: Freedom Is a Constant Struggle

Freedom Is a Constant Struggle

by Angela Davis

Read

Jun 1, 2020 -

Jun 17, 2020

⭐⭐⭐⭐

Freedom Is a Constant Struggle collects several speeches by Angela Davis, as well as a couple of interviews that were done specifically for this book. The unifying theme of this collection is the interconnectedness of different struggles, such as the fight for Black freedom in the US and the freedom struggles in Palestine, which she weaves together through the broader themes of the prison-industrial complex and racist settler colonialism.

The speeches, especially, are inspiring and insightful. However, they don’t go very deep (as speeches of this kind rarely can). The content will be familiar to those who have been studying the topics of racial justice, colonialism and the prison-industrial complex.

Book clippings

It is essential to resist the depiction of history as the work of heroic individuals in order for people today to recognize their potential agency as a part of an ever-expanding community of struggle.

I do think that a society without prisons is a realistic future possibility, but in a transformed society, one in which people’s needs, not profits, constitute the driving force.

If one looks at all of the legislation that was passed, the Civil Rights Act, for example, the Voting Rights Act, that did not happen as a result of a president taking extraordinary steps. It happened as a result of people marching and organizing.

And the Black radical tradition is related not simply to Black people but to all people who are struggling for freedom.

And particularly given the fact that we have the emergence of a Black middle class, the fact that Obama is the president is emblematic of the rise of Black individuals, not only within politics but also within the economic hierarchies. And that is not going to necessarily transform the condition of the majority of Black people.

I think that solidarity always implies a kind of mutuality.

So in many ways I think we have to engage in an exercise of intersectionality. Of always foregrounding those connections so that people remember that nothing happens in isolation. That when we see the police repressing protests in Ferguson we also have to think about the Israeli police and the Israeli army repressing protests in occupied Palestine.

Oftentimes we learn from movements; that happens at the grassroots level and we should be very careful not to assume that these insights belong to ourselves as individuals or at least as more visible figures, but we have to recognize that we have learned from those moments and we want to share those insights.

I think the interconnectedness of antiracist movements with gender is crucial, but we also need to do this with class, nationality, and ethnicity—

At this point, at this moment in the history of the US I don’t think that there can be policing without racism. I don’t think that the criminal justice system can operate without racism. Which is to say that if we want to imagine the possibility of a society without racism, it has to be a society without prisons. Without the kind of policing that we experience today.

It is in collectivities that we find reservoirs of hope and optimism.

G4S represents the growing insistence on what is called “security” under the neoliberal state and ideologies of security that bolster not only the privatization of security but the privatization of imprisonment, the privatization of warfare, as well as the privatization of health care and education.

How can we counteract the representation of historical agents as powerful individuals, powerful male individuals, in order to reveal the part played, for example, by Black women domestic workers in the Black freedom movement?

Regimes of racial segregation were not disestablished because of the work of leaders and presidents and legislators, but rather because of the fact that ordinary people adopted a critical stance in the way in which they perceived their relationship to reality.

Our understandings of and resistance to contemporary modes of racist violence should thus be sufficiently capacious to acknowledge the embeddedness of historical violence—of settler colonial violence against Native Americans and of the violence of slavery inflicted on Africans. Our work today is evidence of the unfinished status of planetary struggles for equality, justice, and freedom.

Any critical engagement with racism requires us to understand the tyranny of the universal. For most of our history the very category “human” has not embraced Black people and people of color. Its abstractness has been colored white and gendered male.

The call for public conversations on race and racism is also a call to develop a vocabulary that permits us to have insightful conversations. If we attempt to use historically obsolete vocabularies, our consciousness of racism will remain shallow

we have to learn how to think and act and struggle against that which is ideologically constituted as “normal.”

The retributive impulses of the state are inscribed in our very emotional responses. The political reproduces itself through the personal. This is a feminist insight—a Marxist-inflected feminist insight—that perhaps reveals some influence of Foucault.

The movement we call the “civil rights movement,” and that was called by most of its participants the “freedom movement,” reveals an interesting slippage between freedom and civil rights, as if civil rights has colonized the whole space of freedom, that the only way to be free is to acquire civil rights within the existing framework of society.

You know, it may be that marriage equality is important as a civil rights issue, but we need to go further than simply applying heteronormative standards to all people who identify as members of the LGBT community

Feminist approaches urge us to develop understandings of social relations, whose connections are often initially only intuited.

our interior lives, our emotional lives are very much informed by ideology. We ourselves often do the work of the state in and through our interior lives.

What we often assume belongs most intimately to ourselves and to our emotional life has been produced elsewhere and has been recruited to do the work of racism and repression.

So we have internalized exchange value in ways that would have been entirely unimaginable to the authors of Capital.

[…] an understanding of what feminists often call “intersectionality.” Not so much intersectionality of identities, but intersectionality of struggles.

But I’d like to point out that Stuart Hall, who died just a little over a year ago, urged us to distinguish between outcome and impact.

Tags: books